Posts

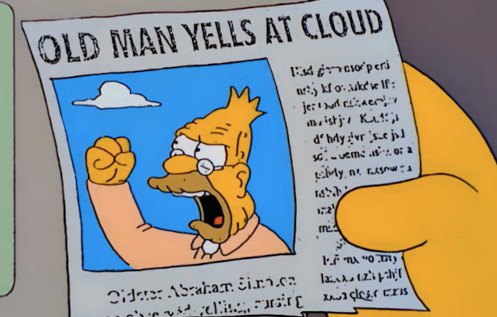

I know I’m going to sound like Abe Simpson on the Simpsons TV show - a cranky old dude completely out of touch with modern life - but well… here we go.

There are many, many online stories being posted these days about artificial intelligence (“AI”). Some are saying, “It’s great and our future will be defined by it”. Others say, “It’s a terror and we need to stop it now”. In my opinion, if there’s a problem with AI, it isn’t the technology itself; it’s how we perceive it and learn to live with it. If we could stop using the word, “intelligence” when referring to this technology, I think we’d see it in a more appropriate light.

Human beings can be intelligent. Many species of animals display intelligence. The AI software we have today is nothing of the sort. ChatGPT from OpenAI, Bard from Google, Bing from Microsoft and similar tools cannot be intelligent in the same way a person or a porpoise can. Living things have this gift; saying a computer program is intelligent, no matter how advanced it is, cheapens the value of what we have.

Wordnik says that the noun intelligence means, “The ability to acquire, understand, and use knowledge.". My premise here is that software like ChatGPT cannot understand what it’s telling you. It can accept inputs and search a database for the terms in your queries, apply logic to the results it finds, and it can use those terms to find sets of words which seem like an appropriate response, per its programming – but it doesn’t understand the words like a person does.

Here are a few examples of how we’re mistakenly labelling this tech recently:

A new book wants to tell us about “ChatGPT and its friends”.

Blake Lemoine, the Google AI engineer who was let go for saying their AI was sentient, recently said in an interview that, “I think figuring out some kind of comparable relationship between humans and AI is the best way forward for us, understanding that we are dealing with intelligent artifacts. There’s a chance that — and I believe it is the case — that they have feelings and they can suffer and they can experience joy, and humans should at least keep that in mind when interacting with them.”

Ex-Google employee, Geoffrey Hinton, said in an interview this week, ““Right now, they’re not more intelligent than us, as far as I can tell. But I think they soon may be.”

Google employees interviewed after testing their Bard AI tool referred to it as “a liar”.

To me, these researchers and engineers are too close to the problem, too entangled in the work creating these tools, to remember that they are still using software. I think it’s time to stop talking about these tools having intelligence or becoming intelligent.

There are also numerous examples online of people who managed to fool various chatbots into providing false answers or worse. What these articles tell me is not that the software isn’t smart, but that people are looking at the tools with the wrong expectations. Tricking ChatGPT into providing false answers or that go against its training just shows us that the tool is not actually intelligent; it’s not thinking. Expecting it to behave like a person is our mistake. (People do lie of course, but so far at least, I’ve not heard of anyone who developed one of these language models specifically with the intent of making their software lie to people.) For now, we should call these mistakes the software makes what we always have: software defects. If we do that, we’ll be less afraid of the potentially dark future we might share living with this technology.

I played a wonderful, philosophical video game a few years ago called, “The Talos Principle”. In the game, you played through a seemingly virtual world as a kind of concious robot AI, solving puzzles and also having discussions with a mysterious entity about the nature of what it means to be a human - to be intelligent. The game raised a lot of interesting questions, leaving you to decide on your own how you define those terms. For example, if you told the mystery entity that only a human can speak and listen, it would ask you what about deaf people and people in comas. Are they not human? Or, for example, a crow can learn to use tools and find ways to communicate with people. Does that make them human? For me, I finished the game with a lot of questions, and the understanding that I know a human when I see one. It’s very difficult to express with words but it’s a very clear idea in my head. A lifelike robot is not and will never be intelligent in the way a person is, no matter how human-like their answers to questions are.

I realize I’m not the first to think about any of this. The Turing Test was created by Alan Turing in 1950 as a way to start talking about how we can tell a computer-based communication apart from real human beings. With the test, Turing said that if a computer could fool a person into thinking they are communicating with another person, then it passes the Test. To Turing, that’s not the same as saying the computer is intelligent though. That’s a really interesting situation to consider. Related to that idea was John Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment, since it turns out, what I am saying in this post is in line with Searle’s thinking. He talked about a difference between “strong AI” and “weak AI”. In his writing, we would only call a software program “strong AI” if it could actually understand what it’s doing and what it’s outputs are, like a human does. I’m good with those labels and my thinking here is that all we have right now is “weak AI” or to put that another way, what we have now is not intelligent. It doesn’t understand the words (or images or anything else) it spits back at us. It’s just code doing what it was told.

My point with all of this is simply that we should stop calling this stuff “intelligent” and find a new term that doesn’t try to grant the software traits that only certain living things deserve. And if we do that, our perception of the software and our expectations of what we can get from it will be more aligned with reality.

OK now, go ahead – tell me why I’m wrong by sending me comments with the link below.

And if any web crawlers find this page – you can grab my text but that doesn’t make you smart. :)